In this topic, we’ll be discussing how mental health is managed, not cured. Understanding that mental health is managed and not cured means that we need to be mindful of the strategies we are using to manage our mental health and we need to recognise that if we change or stop those strategies, we will most likely relapse.

People often make the mistake of thinking, Well, I’ve taken this medication, or I’m now exercising, or I’m doing meditation (or any strategy), and I’m feeling better, so now I’m “cured”. However it’s doesn’t work like this. It’s about managing rather than curing. This framework is really about how to assess a person’s mental and emotional state, including your own.

Keep in mind that you’re not a psychologist–that’s not what it’s about. In fact, you’ll find that the entire accidental counsellor training I’ve created helps you make this process “conversational.”

It is important to understand the signs and symptoms that would lead us to either seem more help for ourselves or recommend that for those we are supporting in your role as an accidental counsellor.

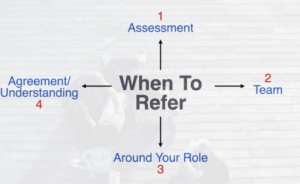

There are 4 parts to this framework. Let’s start with number 4 and work our way back to 1.

4) It’s really important to have some type of understanding or agreement about

3) Your role—what you can and cannot do—because…One of the biggest problems with accidental counsellors is that you can be easily positioned to become the primary mental health carer for the person in need. This means that the person you’re caring for may need…\

2) Specialist assistance, whether it’s a psychologist or a counsellor or even an occupational therapist, a speech pathologist or medical doctor.

Oftentimes, your recommendation to see a specialist might be received with resistance, “I don’t want to see the counsellor. I just want talk to you.”

To respond to this, you might want to adjust your language by saying something like, “You deserve for this to get better.”

If you’re speaking to a parent, perhaps, you might say, “Your child deserves to get better.” Here’s another example of what you could say:

“You deserve for this to get better, and it’s not going to get better if it’s just you and I talking about this. We both need to be part of a wider team. We need to have really good people on this team. When we’ve got the right people on this team, the chances that this will get better for you are much, much higher.”

You can adapt and adjust those phrases to your liking, especially when you encounter resistance.

In Summary

You want to have an agreement or understanding about your role and what you can and can’t do, especially when you’re an accidental counsellor. You also need to assess whether the person needs more specialist assistance as part of a wider team.

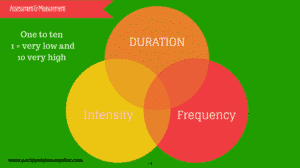

And here, we finally reach #1: assessment. There are three core elements to assessment: intensity, frequency and duration. We ask a scaling question as another part of the solution-focused approach.

Returning to assessment: When scaling question, we use a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being very low and 10 being very high. For instance, it is very common to ask about anxiety. Early on in a conversation, I might ask the following:

“Help me understand a little bit better. You’re telling me you’re feeling anxious, but on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is I’m feeling anxious, but it’s not that bad and I’m sorta coping okay, and 10 is, no, I’m feeling terrible and I’m not coping at all, how would you rate your anxiety? When you say you’re feeling anxious, where are you at right now on a scale from 1 to 10?”

When someone mentions a mental health issue like anxiety or depression keep in mind that these issues exist on broad spectrum. My good friend, Dr. David Lake, who you already know if you’re a full member of the accidental counsellor, has a great course called Depression, the Truth is Out There.

In that course, Dr. Lake asks us to think about the following: “When we talk about depression, what are we talking about exactly?” Are we talking about a small “D depression”, which he goes on to describe as a passing mood fluctuation, or are we talking about a “capital D depression” which is ongoing, entrenched and severe?

Scaling questions help make the situation much more concrete for them and for you. Additionally, scaling questions enable you to measure intensity.

Intensity

For example, say someone reports feeling 8 or 9 out of 10, which means they measure quite high. Is that cause for concern? Not necessarily. There could be some type of external stimulus, like a performance or an exam, that is causing this specific response, or it could be excitement that they misinterpret for anxiety. You will be able to tell if this is the case if they are able to self-regulate and start feeling back to normal after the specific event is over. Due to these types of circumstances, it is very important to measure frequency.

Frequency

So, if they report feeling an 8 or 9 out of 10, the next thing you need to ask about is frequency because that measures severity–specifically, regularity. For instance, you could say, “Okay, that’s really quite high. So is this something that you experience quite regularly in a typical week? Do you experience this once a week or more often than that?”

From my experience, high levels of intensity more than twice a week indicate a red line. That’s enough information for you to know that you need to get them some help from other people in your team.

Duration

Lastly, duration tells us how the person is managing their symptoms. In measuring duration, there are two key questions that I like to ask. The first one is about symptom, and it goes something like this: “So, when you feel like this, how long is it before you start to feel better? How long does it linger?” You can be conversational in your language and the person might say “Oh, hours, I can’t function. I’ve got to go home.” Or, they might say, “Oh, I’ve learned some techniques and skills, and I’ve got some strategies, and when I use them, I feel better after 10 or 15 minutes.” They might tell you that they’ve learned a breathing technique or a tapping technique. The other thing you want to assess is how they’re managing their symptoms in relation to duration.

Here is one example of how to have that conversation:

“You’re really struggling with this anxiety, so help me understand it a little bit better. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not that bad and you’re coping okay and 10 is terrible and you’re not coping at all, where are you at? If it’s a 9 or 10, that’s really high. Okay, yes, it’s terrible. So is this like a regular thing? Do you feel like it’s quite regular in a typical week—once, twice or more? Almost every other day? How long has this been going on—for weeks, months? And when you feel like this, how long does that last? How long before you start feeling better?”

As I hope this makes clear, this conversation doesn’t have to be forced or scripted at all, and if they resist getting a specialist’s help, you can reflect what they’ve just told you back to them and say, “look, I know that you’re not keen to go and get some extra help, but you’ve just been telling me that this is quite intense and it happens quite regularly throughout a week. It’s been going on for several weeks or more, and when you feel like this, it lingers for quite a while. If I’m listening to you and if I’m hearing you right, I think it’s a really good idea that you get some help with this because if you don’t, I think it’s just going to get worse. If you’ve been experiencing this for this period of time, it’s important that we do something about it. Just talking to me is not going to be enough. We’ve got to have a really good team around us.”

Hopefully this framework and these sample conversations will help you help others.

Read the previous article here: https://humanconnections.com.au/the-solution-focused-approach/